1990s

Text by Jochen Gerz

It is always easier to write about looking back (Greek Pieces), as this way society adds new, unsung voices to the tales of denial. Nothing in Europe replaces Greece. Throughout its entire history, Europe remains a tribe of messy (and provincial) Greek casinos. Everybody is ready to fight it out. Europe is a coincidence with a Greek dream. The empire’s only high-rise is “looking back”. Memory speaks up, provides the true story. The truth is the European invention of Greece. Play with the truth, take the truth around and show the truth the new world. New is the world after the war. It is always easier to be new after than before the war. People say: After the war is before the war.

What about art? Is it art? What about literature? Is literature always “life after…”? The spoons are mixed up with the forks, you need both of them but you can also eat with your fingers.

The unsung, formerly invisible and inaudible voices bring about change. The root of our times is modernity of course. This does not change (what was postmodernism?) At the beginning of the 20th century, the new image of poverty concerns a part of society, “naked life” has changed. Society is the new persona. Society is the curse of the industrial age, and the curse is wrapped in a thin coat of poverty. Culture takes sides, culture looks for a new model, culture takes a stand. What do I know? Culture doubts. Culture revisits “naked life”, culture revisits colonialism. Culture has a dream of another society altogether.

The Kulchur Pieces continue the preparation after the Greek Pieces. Prepare for art? This is probably a misunderstanding. Art is the preparation. Getting closer, getting ready – the Kulchur Pieces are, like the work before, about closing in on something else. By doing art you see the world as it is not. By looking at art you see the world as it is.

The Holocaust is not the Holocaust but memory. For the victims it is too late. What happens after the Holocaust is that the knowledge spreads like a slow fire until most of humanity is concerned. Humanity discovers it is stained by what has happened. The knowledge of the Holocaust is another Holocaust. It is as if the German genocide in Europe, in the middle of the Occident, is signed off on by humanity, by the entire old cultural and humanistic elite. Ignorance is not an option, only the knowledge of what has happened offers a choice: most people prefer “to be” victims, others feel they do not have a choice but “to be” in the box of the accused. Both sides feel they inherited an unjust past, and none of this answers the question WHY.

Sharing the knowledge means sharing. It is like an enactment on a stage. The new authors of the new play are the new victims. They play others who are absent, who are not alive anymore and who cannot speak. The others who cannot speak for themselves (or for us today, one is tempted to say) and who need us to speak are our victims. The past is not the past.

What happens after and what does not happen? The evil is not researched. Memory helps to spread the knowledge of what has happened, but it also creates a “local” numbness. Memory does not research the nature and the history of human evil. The perhaps most human fact (the evil) is not the focus of remembering its biggest manifestation. Nor does Memory cry for revenge either. It does not say: an eye for an eye. It turns a blind eye to the joy of punishment as if it were part of the evil. It probably is. Memory maintains an idea of justice claiming that the knowledge of the past is the answer, which somehow “acts” and prevents the evil from repeating itself. Everybody who knows inherits and shares the same punishment. The evil cannot be punished otherwise, since it should not have happened in the first place. The human evil has no equivalent.

But is this a reason not to study the evil, to find out more about human nature and to produce and communicate the results of the most urgent answer to the Holocaust: the international scientific research into human evil? The international community has moved to circumscribe, identify and persecute the evil thanks to new global institutions, but the evil itself is not researched, its cause. WHY. The results of this global research project should define education and make schools the centres of the world. Religion is what it is, an investment in preserving the status quo: tolerate obscurantism; more than half of each budget is spent that way. Is art on the way to following in its path?

The monument to the Holocaust should be the research into the nature and history of human evil as what is by now the most defining circumstance of life on the planet. The results of this research should be applied. This is, this would be memory at work.

Post-war society, not only in Germany or even in Europe but mostly there, embraces the idea and feels the need to face and to make the absent new author, the victim of systemic injustice and suffering handed out “by us”, known in that way: The acts of individuals are not only done by themselves but also justified by an ideological framework, the author of which is a state. That state can change. It has reversed from democracy to dictatorship and from dictatorship to democracy.

Democracy has been lost before and can be lost again. A part of the advent of or the return to democracy, which often is the consequence of a defeat in a war or a capitulation after a revolt, is the public will to transfer the responsibility for the dictatorship state (as a memory) to the new democratic nation; that is, to each of its citizens as members and shareholders. This transfer is the reason for the emergence of a new kind of memory, which is personal as much as collective. Of course there are discussions among academics on whether there can be something like a collective memory, a memory transcending time, a memory held by those born after. Memory here not only means information, debate and knowledge (and not denial) but responsibility and also guilt. Can you be guilty of what your parents, grandparents, ancestors did? This debate is academic and at the same moment it is not contained.

It is not contained in two ways. In Germany itself, the post-war society does not hold the old tribal, class or other identities anymore. Are they destroyed at that time? Their reconstruction takes more time than the rebuilding of the economy and the cities. The rebuilding of the German economy is not only a local success but also a global reality. The memory of the war is defining the new fact but is also defined by it. The academic debate is an agent of the “new”, and more generally of the cultural. That is why with time, first in the West and afterward also in post-communist Eastern Europe, the challenge of the coexistence of the new that defines the old, and the old that constantly redesigns the new, is met. But at the same time the idea of a return to the old order, a past that never existed, is present. There are two names used for what many people consider the same threat to democracy: religious terrorism and secular populism. They pretend to fight each other and they pretend to fight for “us”.

What is just as relevant as the above: the “undeserved” freedom and the return to democracy leads to an almost natural modesty not only on the part of the state but also its citizens, civil society. And part of that “national” modesty (again, not in Germany alone) is the readiness to remember the Holocaust not as a historical and geographical event but rather as a lasting stain on humanity. Not a stain on them but a stain on us. Civil societies in Europe see themselves as pacifist. This is even more so the case with Germany. The unassuming, almost demilitarised state (which exports the most sophisticated weapons and has them tested in tribal wars far away from home) and its modern people deal with the return of atavism; the states without a death penalty deal with their kamikaze children. The homecoming of the exported violence to their places of origin begins before the end of the century.

Is it possible to lose modernity (at the end of the American century)? Europe experiences a challenge to its order, which has been the foundation of the relationship between its nations and people since World War II. The East, the Communist Bloc with its relative delay in economic development, stands for a different reading of the same reference. Since the fusion of both blocs, West and East, the two readings of modernity have been fusing, too. The new reading is “modernity as a quote”. The word “revolution” has never been used as often before. The use of a quote stands for a diffuse desire to market a past, to make it present, to recall a past. It is like most desires not a radical, hands-on departure from acquired ground. On the contrary, it is feeding the need for a slowdown, for the status quo. And it is looking backwards, not forward. The desires for the future and for the past share the same applications. The need for the past as a quote is what both have in common. The quote of modernity as a future prepares the ground for the right of others to quote their own past.

The forbidden past is the end of democracy (state fascism and state communism). This is the change happening at the beginning of the 21st century: both pasts return transformed into quotes, both claim “the lesson”. Memory is the lesson. What is new: not only one side claims memory (not only one side is cultured), but also others claim memory and offer quotes. Many sides. Some quotes are acts. Some people do not organise debates and symposiums. They call it a war, they force people to say “we”. Some people call it terror. Others act in the name of a kind of community some often talk about. Not a state, not international institutions but rather a state of belonging. People talk about conditionality. People call a theatre piece bloodless. People are out to win the war of desires. People say: It happens in the name of God.

Perhaps all looking forward is looking back. The new is the origin. This is another quote (Karl Kraus). Of course there are always rumblings at the fringes of Europe, but in our brave old world of duality, most people respect the words that hold everything together: never again. Most people are cultured that way. The Cold War is not war but peace. As much peace as you can expect from history books full of violence, from a world order totally inexperienced in keeping peace. Yet it is a time of peace. Everything, including art, lives and blossoms in the shadow of the nuclear threat and memory. At this moment in time, most people still think that all sides are both sides, and both sides share the same reservations. It is the common origin, (the deadly past): standing together in the fight against oneness, capitalist imperialism (rather than against populism, against inhumanity).

The questions of freedom and democracy only slowly start to eat away at the Cold War order. Freedom means something historical, a common reference. In an almost private way it signifies the growing awareness for justice and civil rights, but politically and internationally it means economics. This goes for democracy, too. It can be said that communism collapsed because of economics, but culture was also a reason why the Cold War was won. The unification of the world and the beginning of the end of the system of duality is economic and cultural. The unstable liquid coalition of the two, economics and culture, follows the stable Cold War opposition. But consumerism is not a programme for government. It is not geographical. It is driven by the needs, alienations and fantasies of consumers, i.e. populations. The new order hates fences. The new order is a melting pot, it is dynamic bric-a-brac. Even the rich start to buy fake stuff and to look like fakes. They dress like tramps. Nothing is what it is, but almost everything can serve as a fitting quote. Art is not an exception anymore.

After the end of the 20th century, all sorts of political initiatives aim at creating new blocs, new economic and cultural lobbies. Whatever the basis of these blocs or coalitions with or without treaties, they are not stable, they cannot anticipate or freeze the unpredictability of economics. As if economics were the last bohemian refuge and outlaw, the fighter for creativity, freedom (and culture) wanting to break its chains. As if the whole world wanted to unite, trying to reason with economics and to make this last Gulliver understand a (new) rationale: creativity or violence, freedom or violence, culture or violence.

The search for a peaceful consensus, binding for all, is frantic. It is the new global search for food, for survival. In the midst of these myriad short-lived global expressions, creations, emotions, ideas, NGOs and petitions, economics toss and turn in their sleep, having bad dreams of freedom. Maybe the non-violent helpers, researchers and givers who reason with economics and urge it to try to understand and follow new rules are themselves the future of economics. Awareness.

The Other is the new word for freedom. Is art in the cultural society part of the old fight of economics for the freedom of distribution, for profit (and inequality), or, on the contrary, is it part of the growing number of petitions, of protests, initiatives, concerns and manifestations by unknown helpers, authors and followers who want economics to change and who promote an economics of sharing? It is part of both. Art also shows a misunderstanding. Art shows that economics are not the economics of objects but the economics of thoughts and purpose. Some people call it education. It has always been that way, even if we throw objects, pictures or bombs at each other. This misunderstanding stands trial again and again.

What he remembers and how he remembers is a negotiation that seems to take place without him being in the room. He does not know what is at stake and he does not know the participants. He tells a story. He tells a story he does not need to tell to himself. He does not need to tell it to himself since he remembers. He tells a story to somebody else. What does somebody else have to do with his story? They were not there. They do not know what has happened. They do not know the truth. This is the reason for the story. They do not know the story. The truth is not the story. The truth of the story is another story. And the story of the stories is that they may have changed since the others who listen or read are not in the room when the negotiation takes place. When the story is told. Invented is not the right word. Created would be a shortcut too. Where does the story come from? Not even he who is telling the story is there, until he remembers. When he remembers the story, the story remembers him.

That is why it is called a gift. It does not stand up to science. It does not stand up to the truth. It is a concept that acknowledges time. Time is a marketplace where all that is spent is returned. Time is a bird that has memory in its beak. Time is a raven flying up high in the sky and dropping memories, a story, time and again. “Fish be a giver,” sing the Kwakiutl when they take to the sea. It is not about identity. The concept of giving can be tempting. It is not the opposite of taking, as one might think, but taking is part of it. Taking is not why life dies and giving is not why it is born. There are cultures that side with giving more than taking, and they see themselves as being part of the concept of gifts. They say, don’t look further.

Others are attracted by the fear of losing out, the fear of missing something. They are good at looking for reasons. They are short of time. They want to stop time.

Gradually the gift is understood as a return on investment, which it is; as a means of sustaining profitability and consumption, which it is. It would take some statistics to explain this … if the raven (his own time, his own memory) would not fly by and gift him with a dropping. Why do people say all of a sudden: Keep it in the ground? Memory is an intuition. The concept of giving, as a way of returning, is nothing less than an act of balancing the books, a quite normal act of accounting. To give and to take needs time, and memory is a link. For some it is a new story, for others it is an old story that cannot be told twice. They call it imagination.

The story to be remembered comes “out of the blue”. It is the authentic story about a time “outside of time”, before politics, in a place between the sea and the mountains, a land broken up into many small islands. Whoever makes it to see their neighbours is happy and meets for the day. They speak some fifty languages in that area; everybody seems to have their own language, spoken only, and everything is part of the stories, the authentic story. It is Babylonia, but they have something, so much in common. It is potlatch country, and what is known about them is little enough, and often contradictory in other people’s minds, people from other places, from other times. It is all about the visits in wintertime when people take to their boats and meet their neighbours.

The boats are full of people, otter skins and dried fish. They travel across the sheltered water or the open sea to meet their neighbours, often for days. Once they get there they are exhausted but very much welcomed by their neighbours, whom they have not seen during the busy fishing season, the whole year, and the meeting begins. Some call it a feast. The guests have brought with them a singer or storyteller. He will make up a song and praise the neighbouring chiefs and their people, how they are living in peace, how they care for each other, how they are wealthy and respectful of nature.

Nature is what they call the giver, and everything depends on its mood. There is no need for nature to be a giver. There is no religion to challenge nature. Especially the salmon needs to be a giver, and that is why they also sing songs when they go out fishing. Everything around them has its song, its right time and its reason and needs to be a giver; it is never easy out there on the water but they know it from their own experience and from many older people’s memories. Nature is what it is, it is unpredictable and they need to think about it all the time and that means they think not only about now, but also about yesterday and tomorrow. That is what the visiting neighbour singer sings about and that is what their hosts and neighbours like to listen to.

You could say it is always the same, but for them it is as new each time as any printed news for us. One year the Haida people from the north take to their boats and visit some Salish people on the south coast, the next year it is they who are visited by neighbours from the Nootka Sound whom they may not have seen in a generation. Some stories are always told to praise the hosts you may never have seen before. One could say it is all about the stories, all about resemblance. Neighbourhood is everywhere. Nobody lives far enough away to be left out.

Part of the meeting some call a feast is the distribution of the otter skins. They are piled up in front of the chiefs’ place and the welcoming people in praise of their way of living that gifts them with everything they could think of. They name all of it, one by one. The naming takes time. And each time, a new otter skin is added to the pile. It is all about gifts, but the gifts do not come for free. Another year, the visitors will be visited in return and this time the visitors will be the hosts. They don’t know when.

Next time, it is they who will listen to the stories of the singer. They will be praised and will receive lavish gifts, the exact number of skins or even more skins than they gave away to their neighbours when they were the visitors a while ago. The rules have stayed the same for a long time. Everybody seems to know the rules. The more you receive, the more you are expected to return. For some people it is a cruel affair, even though the rules are the same for all. You share what you know. It is an important part of what they all have in common. Why the skin of the otter? They do not eat the otter. Is it the beauty of the skins, their warmth as a covering and clothing, or is it because the otter hunts fish? They eat the salmon and the salmon is also part of the gift. They give away in order to receive, but what they receive is also part of their gift. What they eat and what they give away is part of the return. The praise they heap on their neighbours rewards the respect they show for the rules. The rules they have in common, the rules that run the world. And what is the world? The world is not an invention. The cruelty of the gift makes sure the rules are in place, so the world will be a giver in return. And in return they need to match the gift.

Does this place exist? Will this happen one day? Is this the story of the potlatch or the story of the origin of the stock market? Does he need to go there or did he at some stage read about it in a book?

The second body of works, the “invented communities works”, are done after the “authentic stories”. It is about the same place but another time. The first is about the place as a timeless state, the second (same place, but in the 1990s) could be described as social. Both parts deal with people. The first is about people surrounded by a wider display of forces, mostly invisible and present only through the thoughts and memories of people, their authentic stories. It is about what they share, their rules and common attitudes.

The second part also deals with people. People’s environment has shrunken somehow. Many things are not only material and visible but also out of use: forgotten, discredited or accessible only through individual or social memory and trauma. What people speak of can be proven; it is part of impartial scientific, historical or academic evidence. What matters for people are the things they do not do themselves. As a consequence of this, they have a tendency to fight over and criticise in their communications what is wrong and what is fake rather than to stand up for what they do and what they consider just and true. Fiction is king. People have to evoke solidarity all the time, as most of the decisions are individual one-off decisions. Each day is new. They want to be free. Nature is not a big issue; most of the time people deal only with themselves.

Their world is a world inside another world, and each world inside others is a more predictable reflection of the wish to further the transparency and knowledge of the world. The smaller it is, the higher are the standards of perfection (and the demands for it) and also, the more the world’s imperfections become a concern. Their obsession is the making of an endless and complete list to fix the world (the world of people), its evils, injustices and other shortcomings. It should be mentioned that the wish of people at that point comes true: their world is indeed more immaterial by the day (remember the “authentic stories”). So before turning immaterial, the world of the people also has a wish and a dream: Please don’t let me run out of space. And as dreams by then have come true, science confirms that in the digital world there are no problems with space. So the world is the people’s wish list, which can be pursued unchallenged and without erring or faults, as it does not run out of space. Humanity’s memory can continue, repair and update itself a long time after people, a long time after oblivion (Google: The right to be forgotten). A long time after time.

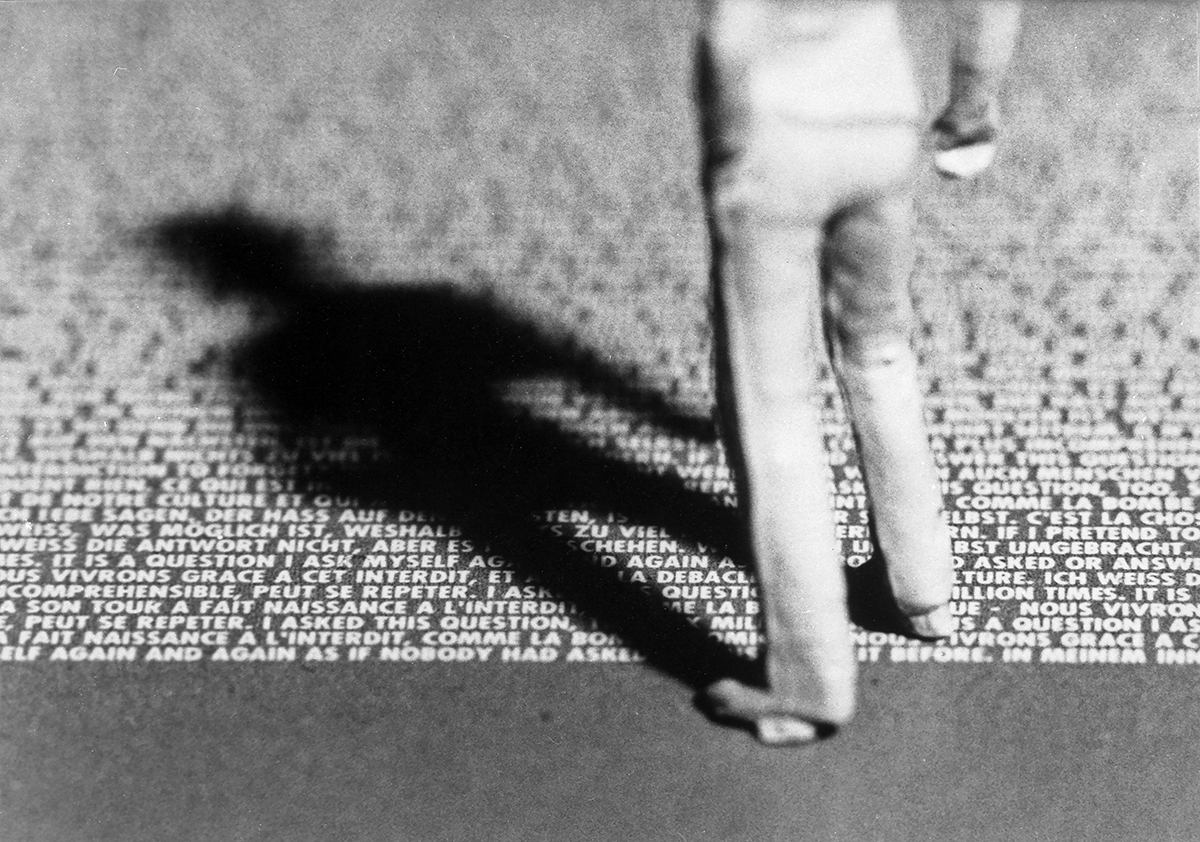

The second part of the Mixed Media Photography looks shattered, exploded, aggressive, big. The friends of the tiny Photo/Texts from the early seventies don’t like them.

These works are desperately loud, they are all over the museum; they are metastatic. They are turned toward the viewer like a loudspeaker. These works look as if they were shouting at people. As if they wanted to make them wake up. The geese of the Capitol. They are the last works done for a wall. They are not for liking.