1940s

Text by Jochen Gerz

ABC Radio Sydney 1984: I had a happy childhood. Dare one say this? Whatever happens afterwards, childhood comes first. Otherwise, he does not remember much. Later on they would repeat, again and again, that they do not remember. A few years later they say: Souviens-toi. And: Never again. What they told him later... nobody tells him: the war has started and father Alfons is a soldier in Poland or France. He had better ask if he wants to know.

They, who are they? Nobody tells the story. He does not say that he missed these years, that he was only a child. Nobody asks, nobody answers. They. Who speaks inside his head? He needs to find out whose voice it is. It’s war, Jim, says Stanislas to his brother in Zurich, and Joyce replies: I told you, I have a problem with style.

Whatever you say tends to become bigger, as if it were not enough as it is. What story do you have to tell? Telling is selling.

The French and the English blitz the village, the Americans come later, and they stay. Curfew: They take prisoners in the schoolyard, they have chocolate. Who is milking the cows? Uncle Arnold hiding among the potatoes.

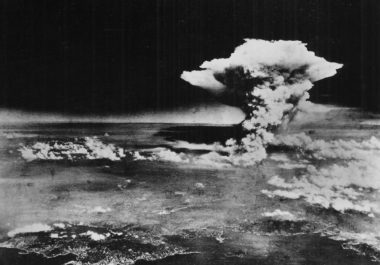

From what age does he have memories of the time before? Waiting. Sitting on a crowded train. From what point in time does he look back? The heat and the cold. Watching rows of houses burn and collapse nearby and far away. Since when does he remember the smoke, the ruins, the piles of rubble? And who had a happy childhood? Whose pictures are these? Who remembers? Who speaks? Leaving Berlin. Escape amid fractured voices – today we know this from TV. The news. Deception. He remembers the teacher’s wife, the neighbour’s waffles, Frau Göken listening to the radio in the kitchen: her smile. Someone escapes hanging. A smile.

He does not know Nuremberg, he does not know Göring, the man who escaped by poisoning himself, but he understands that he does not know. His own life.

He does not know that 98.8% must be wrong. Over the years this becomes even crisper, sharper: memory like an ersatz, a substitution at the launch of his generation. He cannot be the only one to know, either.